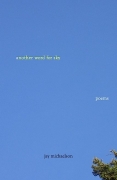

reviews and praise for another word for sky

reviews and praise for

another word for sky

by Jay Michaelson

Ilya Kaminsky, author of Dancing In Odessa (Tupelo Press, 2004) and winner of the American Academy of Arts and Letters’ Metcalf Award:

Jay Michaelson is a poet of multitudes. His gift is not just his enviable ability attain the poetic voice very much his own, but also the skill to use this voice in poems that are quite different form each other and can speak on different levels at once. This skill to do many different things well is, I believe, quite rare in poetry of the generation to which this poet belongs.

Michaelson possesses a lyric voice of a poet who understands that “a simple car ride brings it all back / with bold classical music on the radio.” So, what, in the end, can it bring back? The lyric moment of peace into these days of ours, both terrified, and dizzying, and in much need of such lyricism. Michaelson in the early poems of this volume is “flirting with the unreal, dipping his foot in, dangling it.” He makes us suspect that “January remembers June” and “magic is still possible.”

This lyric meditation alone would have been more than enough for many poets. Yet, for Michaelson, this is just the beginning. His lyricism by the middle of the book begins to break into prayer, in such beautiful pieces as “What’s Another Word for Sky” or “Pure White Blue” or “The weight of the sky.” Each of these poems gives us the lyric moment, and yet, at the same time, it approaches the prayer-like territory.

And yet the realm of prayer is not where Michaelson is about to stop. As we read on, we realize that his relationship with the divine is filled with Amichai-like playfulness, which knows all too well that our life is a wedding and a funeral, at the same time, in any given moment. And, so the erotic on these pages comes hand in hand with the devotional. I love such gorgeous poems of his as “Only One Lover,” “Yes, I am Checking You Out on Simchas Torah” and “It says ‘woman came out of the man’ and I am putting her back.” I love how the playfulness of tone and the linguistic pleasure of saying words slowly, saying them aloud, repeatedly so, come together in these poems, along with the (very Jewish) utter need for the erotic and divine to get mixed up, messed up, most lovely so, and sing.

But even such exuberant playfulness is not his limit. I admire, for instance the very different, somehow melancholic sort of playfulness in the stanzas of “Foot Pain”\235 and “What Eduardo said.” And, I also find myself drawn to the strangeness of his “Visitation # 3\235,” and most of all to the mysterious, alive and unforgettable poem, “in praise of isaac, of whom it is said, he knew what it was to be a woman,”\235 which may prove to be one of the strongest poems in Michaelson’s generation to have placed the claim on the holy book.

Alicia Ostriker, author of The Nakedness of the Fathers and The Volcano Sequence:

They say shamans can be in two places at once–the material world and the spirit world. Jay Michelson can be in both those places at the same time–and more. He is a post-Wittgenstein philosopher, a ravished mystic, a queer Jew, a comedian, and a dazzling poet. Sometimes you will find him, like Whitman, loafing and inviting his soul. Sometimes it feels as if he is walking barefoot on broken glass or on burning coals. I salute his passion, his boundary-breaking, and the ceaseless vitality of his words.

Richard Chess, author of The Third Temple and poetry editor of Zeek: A Jewish Journal of Thought and Culture:

To his many list of talents, Jay Michaelson can now add gifted poet. Another Word for Sky, Michaelson’s first book of poetry, moves from Wordsworthian reflections on the seasons and nature to tender love poems to Ginsbergesque satirical rants to devotional poems in which eros is the power that distracts or concentrates one’s attention on the worthy object of one’s desire – God or man, or God embodied in man. Given the breadth and depth of Michaelson’s learning, as he so ably demonstrates in essays and reviews he publishes seemingly on a daily basis in prominent places such as the Forward, Nextbook, JBooks, and Zeek, one might have expected a kind of cool, intellectual, smooth poetry coming from his pen. While these poems definitely reflect Michaelson’s vast body of knowledge, alluding especially to poets and writers in whose company this book will live, their more prominent feature is their high energy expressed in fast moving leaps of association that dazzle and unnerve a reader with their sudden illuminations. From the nightmarish “Purim 5756” to the provocative “Stop the School Violence,” in which the poet calls for ‘the mandatory,/ forced/wrapping/ of tefillin/ on every schoolboy in America” as its solution to this national problem, and to the emotionally wide ranging “An American in Jerusalem (Just what this country needs),” the poems on Jewish subjects are especially energetic and fresh. If you are comfortable in your pew, these may not be the poems for you. But if you want to see “Puff Daddy in Fiddler on the Roof” – and if you want fully embodied poems of outrage and love – and if you want to “make a religion of flaw,” read Michaelson’s “Another Word for Sky.” You won’t regret it.

Jay Michaelson’s poetry in Another Word for Sky his newly published volume of verse, draws you immediately into the poet’s private world. His lyricism pulses, and his dramatic realism is quietly volcanic.

One can find oneself reading ‘sky” aloud just to hear its cadences, like Tantric seeds sounds on frequencies one has to be alert enough to tune in. This verse enters your body. Consider this passage:

The proposition I would present to you is this: There is space for a wide-open skylight, for the cross-beams of light to pattern the architecture of disappointment,

He invites you into his imperfect realm of beauty, eroticism, spirituality, curiosity and human struggle and failing.

Michaelson sustains an intimate tonality that frames even obtuse sketches of people and place, but always with economy and concrete imagery. Catching an autumn tree line in a car listening to classical music so bold, it “Makes me forget poverty and loneliness.”

He is unflinchingly brutal in a blistering commentary the prevalence of anti-Semitism “An American in Jerusalem” and reveals the might of his poetic power in a piece like ‘the knowing” with lines like

‘the thinnest meridian of an instant/This most transparent love.”

In fact one doesn’t even have to know that Michaelson’s previous volume of poetry “God in Your Body: Kabbalah, Mindfulness and Embodied Spiritual Practice.” to understand that he is a deeply spiritual man and a voluptuary. Some of his relationship poetry is whisperingly erotic without any mechanical literary devises, or predictable explicitness.

…His brilliant social comedy “Twelve Tribes of Israel: a true story” investigates the rituals of gay male Jewish dating with the ending salvo-

Let the boys come home/To each other

I call you now, my brothers-

We are not all/Accountants.

Michaelson, national community organizer for Jewish GLBT people and editor of “Zeek: A Jewish Journal of Thought and Culture” promotes inclusiveness and understanding. Michaelson is a compelling polemicist with such titles as “Keep Your Godwrestling, Thanks: The Uses and Limits of Theology.”

With such evocations Michaelson’s “another word for sky” reveals a vivid poet blessed with a prismatic voice.

– Lewis Whittington

Rachel Barenblat, Velveteenrabbi.blogs.com:

Yes, I am checking you out on Simchas Torah.

You are sweating, you are dancing, your breath stinks of vodka,

Your white shirt is plastered to your chest,

Its buttons are partly undone,

You look like an entrant in a Yeshivish wet t-shirt contest.

That’s from one of my favorite poems in another word for sky, a collection of poems by Jay Michaelson (Lethe Press, November 2007.) The poem is wry and startling, deliciously grounded in physical detail, and very, very Jewish. (So’s the collection.)

I can’t help reading the poem through the lens of Hasidism and homoeroticism, an essay of Jay’s that I read in Zeek back in 2004. But the poem goes places the essay doesn’t, and there are all kinds of reverberations and refractions for me in the spaces between them. Same goes for another of my favorite poems in this collection, “Foreign Thoughts,” which begins:

I don’t feel ashamed

when I spy you at the mikva,

out of the corner of my eye —

a body is a body,

and wants what it wants.

I love that it’s when the narrator catches a peek at the object of his desire davening, in intimate connection with God, that he is abashed. Seeing a beautiful body is one thing; visually eavesdropping on a conversation with the Infinite is another. The poem gives a whole new cast to questions of boundaries and transgression. It knocks me flat. I want more.

I’m picking and choosing, here, as every reviewer of poetry does. A different subset of poems would give you a different impression of the collection. New York poems. Seasonal poems. Poems with long lines. Linguistic playfulness. Maybe another year those will be the poems that grab me and won’t let go. But this winter it’s this particular intersection of Judaism and eros that excites me.

In “in praise of isaac, of whom it is said / he knew what it was to be a woman,” Jay opens up the story of the akedah, the binding of Isaac. He makes Isaac’s ultimate act of submission plain in a way it had never been for me before. The poem is disturbing and tender and erotic — as is the original story, frankly, or at least it is for me now that I’ve read these lines. “isaac is the fulcrum who gives himself over,” Jay writes. “isaac is the yielder and the receiver of love.” Holy wow. Something tells me I’m never going to hear that passage again in quite the same way.

That’s part of the genius of this collection, for me. That’s Pound’s eternal dictum, “make it new” — practically the house motto at Bennington, at least during the years when I was there. These poems take words and concepts that are familiar to me, and show me something in them I hadn’t seen before.

These poems don’t shy away from difficult subjects. Here’s another taste, from the poem “When I see the word ‘Israel'” — to which I’ve returned more than once already in the few weeks since I first sat down and read the collection:

When I see the word

Israel

I see

Isra-el

wrestles with God

God is

victorious

When I see the word

I do not see

the chosen few

I see those few who choose…

Those who say

I betroth myself to you

whether it feels like honey

or a thornbush

Jay knows, this poem knows, that over time relationship with God inevitably feels like both of those things. Every religious peak moment is matched with times when the One is so veiled there’s only a palpable absence. And with times when relating to God, relating to tradition, is just plain painful. Being Israel is about the existential leap of choosing the relationship, even though — even when — it isn’t easy.

Writing that out in prose feels preachy. The poem is better. Read the poem.

Alicia Ostriker is one of the poets whose words appear on the back cover of the collection, which makes perfect sense to me. Her work too delves into the rich mines of Torah and midrash, forging that ore into something startling and new. She does it with criticism, and she does it with poetry, and I’ve always had the sense that the two branches of her work feed each other. (That’s kind of a theme for me at the moment, for what may be obvious reasons.) Same goes for Jay, and I suspect it’s one reason why there’s such a clear alignment between his work and hers.

To choose to be a Jewish poet, defined not by birth but by subject matter and personality, is necessarily to render one’s experience in terms of symbol and myth. One becomes as if infected by Jewish language. This is a perilous undertaking, as a poet’s task is necessarily to see things in a new way, while the Jewish words pull toward the old, as well toward the cliché[.]

So Jay writes (in People of the Chapbook, which touches on Ostriker’s work and also on the new book of prose by Rodger Kamenetz who I’ll be interviewing for Zeek later this spring.) Perilous it may be, but he pulls it off.

Best of all — maybe the reason why this book rings so many bells for me — is the way these poems celebrate not only our texts but our endlessly-changing relationship with them. As it is written, in “Juicy:”

When you are studying

you involuntarily open your mouth

just a half an inch

as if to drink up

the juices of the text.

This is one hell of a juicy collection. Go and read.